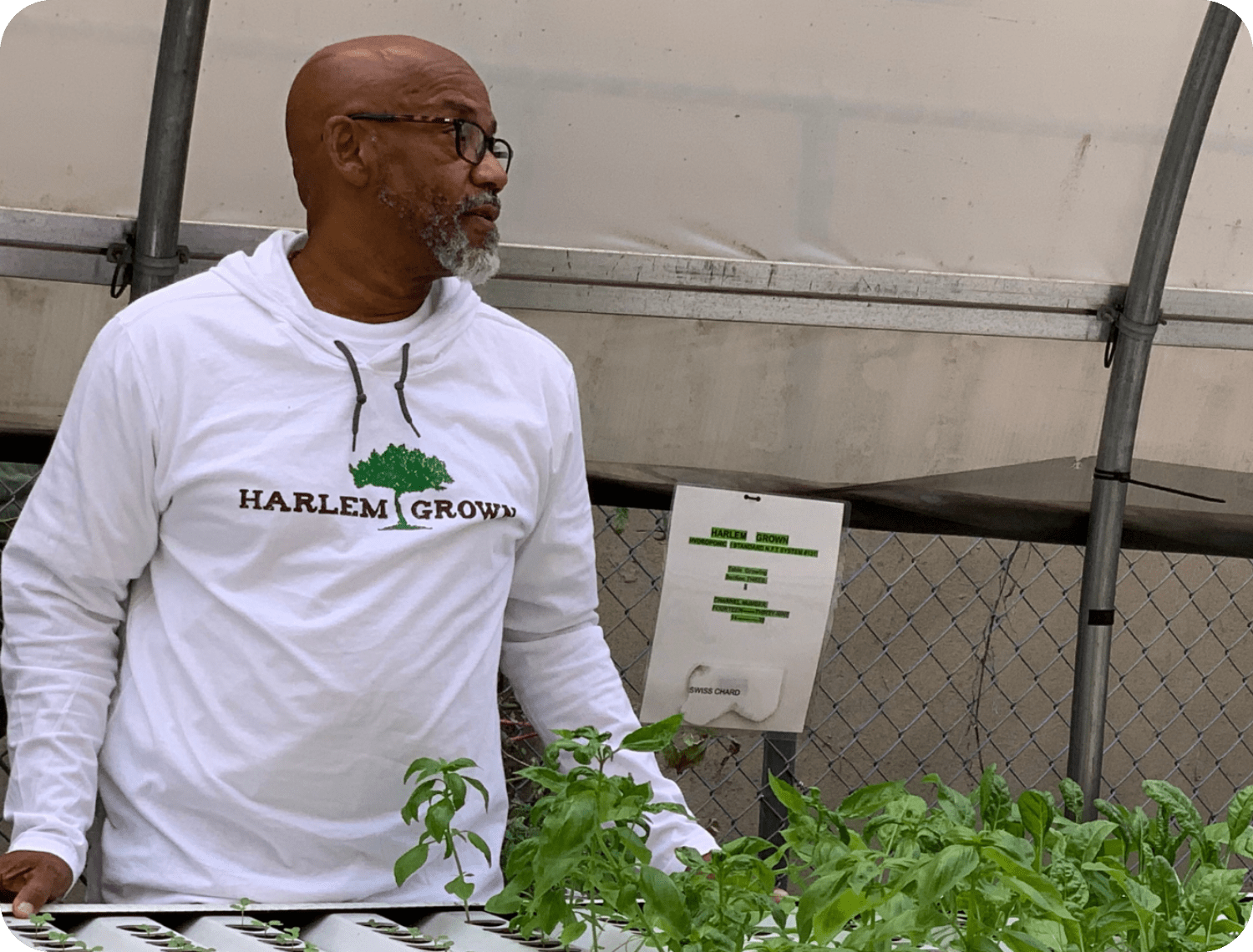

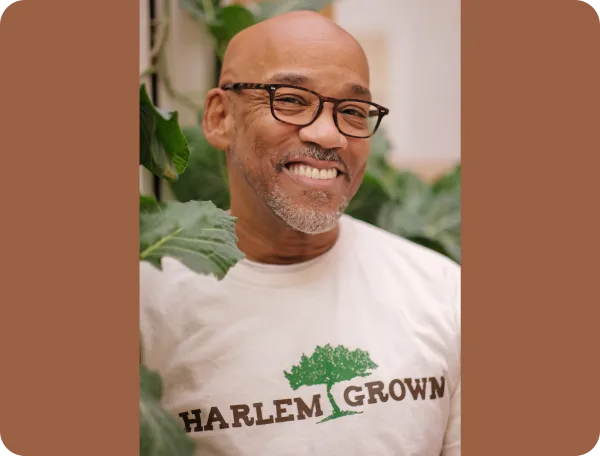

“There are no green spaces close to where they live… But in the garden they notice the birds, the butterflies, the ladybugs, the worms. Our gardens are little oases in the middle of the chaos of New York City.”

Tony Hillery, Founder and CEO

Harlem Grown

For many parents, getting their child to eat a mushroom is nearly impossible. But the team at Harlem Grown, an urban farming nonprofit, has figured out it’s the same way you get kids to eat kale or okra or zucchini. They plant it themselves, grow it, pick it, and smell it being sauteed in garlic and oil. “The next thing you know, we’re eating mushroom tacos and mushroom burgers, and that’s how you do it,” says Tony Hillery, founder and CEO of Harlem Grown.

That’s how the nonprofit has been doing it since 2011, when Hillery first rallied a local school and neighborhood to turn an abandoned community garden into a thriving urban farm. Now with 13 urban agriculture sites—soon to be 14—including six partner schools with gardens across Harlem, it grows 6,000 lbs of organic produce a season, including 50 to 60 lbs of mushrooms a week. All that produce goes straight back into the community free of charge to residents. Harlem Grown combines a variety of programs, including weekly Saturday programming, a 7-week summer camp, an afterschool program, farm-based education tours, monthly community events, and a Mobile Teaching Kitchen. It promotes, alongside its partners, sustainable and healthy communities, and food justice for children in Harlem.

We recently sat down with Hillery to talk about food justice, breaking the cycle of poverty, and the joy in watching kids adopt a love of nature and growing foods.

You’ve said that food justice begins with education. Can you explain what you mean by that?

You can give away all the food in the world, but if people don’t know what it is or how to prepare it, it’s going to be wasted. We specifically target elementary school children because healthy habits need to start young, and there’s no better way than to get them in school when they’re already learning. I’ve been doing this for 13 years and I’ve yet to meet one parent who doesn’t want three organic meals a day for their children. But it’s a supply and demand issue—the supermarkets won’t stock kale if they have to throw it away after two or three days. That’s where the education component comes in. We teach our kids how to cook with the ingredients and they ask their parents for them. It’s a slow burn, but it’s working. Everything we grow is given back to the community, free of charge, but it comes with nutrition education, cooking demos, and recipe writing. When we give food to the participants, they know what it is and how to prepare it.  Tell us about how you partner with schools and host field trips and classes at your urban agriculture sites.

Tell us about how you partner with schools and host field trips and classes at your urban agriculture sites.

Every school wants a school garden and garden education, but they don’t have the resources or manpower. First, you need three people to support the program—the principal, the parent coordinator, and an active parent. Then you have a sustainable system if one of them leaves. But once we have an agreement with the school leadership, we do everything else: lead the classes, maintain the garden over the summer. All Title 1 schools are invited to our farms for free, and we strongly suggest recurring visits. The teachers hang back and our educators break up the kids into small groups and explain to them the difference between a weed and a seedling, an invasive plant and a beneficial plant. Once the kids are comfortable, they ask a lot of questions!

When Harlem Grown establishes a garden and the students get familiar with growing things, what do you see start to happen?

We bring the first- and second-graders in to participate in the garden design because they’re going to be there for the next three or four years and we want them to feel ownership. But what’s amazing is how fast they adapt. First they say, “It’s dirty, it’s stinky, there are bugs.” But then it just flips and they come in to look for the bugs and pick them up, to be the first one in to chop up food scraps and turn the compost. And they notice how time slows down, how quiet it is just off the sidewalk. There are no green spaces close to where they live and everything is at a hectic pace—that’s poverty and it’s very stressful. But in the garden they notice the birds, the butterflies, the ladybugs, the worms. Our gardens are little oases in the middle of the chaos of New York City.

You’re about to open your 14th oasis in the city. What can you tell us about it?

We’re building a multimillion dollar, state-of-the-art urban farm on Lenox Avenue, anchored by a freight farm, which uses hydroponic systems retrofitted for a freight container. We’ll be able to grow an acre’s worth of food using just six gallons of water a day. We’ll also have a 30-bird hen house and a solar-powered teaching kitchen. But the most exciting thing is that it’s at a senior citizen housing center and we’ll be introducing intergenerational programming to bring the seniors together with the children so they can farm and learn together. We’re planning to open the first week of May.

Harlem Grown has been operating since 2011. What is your ultimate goal?

The ultimate goal is to break the cycle. I have kids that I started out with that are in grad school or about to enter college. I want to hand over the reins. Our first college graduate is now in grad school getting a degree in social work. Hopefully she’ll come back here and be part of the decision-making process. I’m not Harlem Grown, I wasn’t born here, but the children here are, and if they want to come back and take over, that would be full circle for me. Like I say all the time, we plant fruits and vegetables, but we grow healthy children in sustainable communities. That’s our biggest crop and what we’re most proud of. We grow children. We grow people.